Zhang Xiaogang's 'Big Family No. 9'

by

Megan Lee

“Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.”

The opening line of Leo Tolstoy’s Anna Karenina seems to suggest individuality, the trait that makes us human, is also what exiles us from happiness.

What might seem like an exaggerated premise for a dystopian novel, was the harsh reality of the Chinese cultural revolution launched by Mao Zedong in 1966, and lasting until his death in 1976.

Historical context

What began as a way to preserve Chinese communism by purging remnants of capitalist and traditional elements from society, quickly turned into a violent campaign that included myriad incidents of torture, murder, and public humiliation. Individuality was replaced by communist collectivism, creativity was replaced with the depiction of propagandistic subjects and the heart of Chinese culture was replaced with a cult of personality.

Even years after the tortuous decade, the devastating ramifications of the revolution are and will be forever immortalized through the works of Chinese artists.

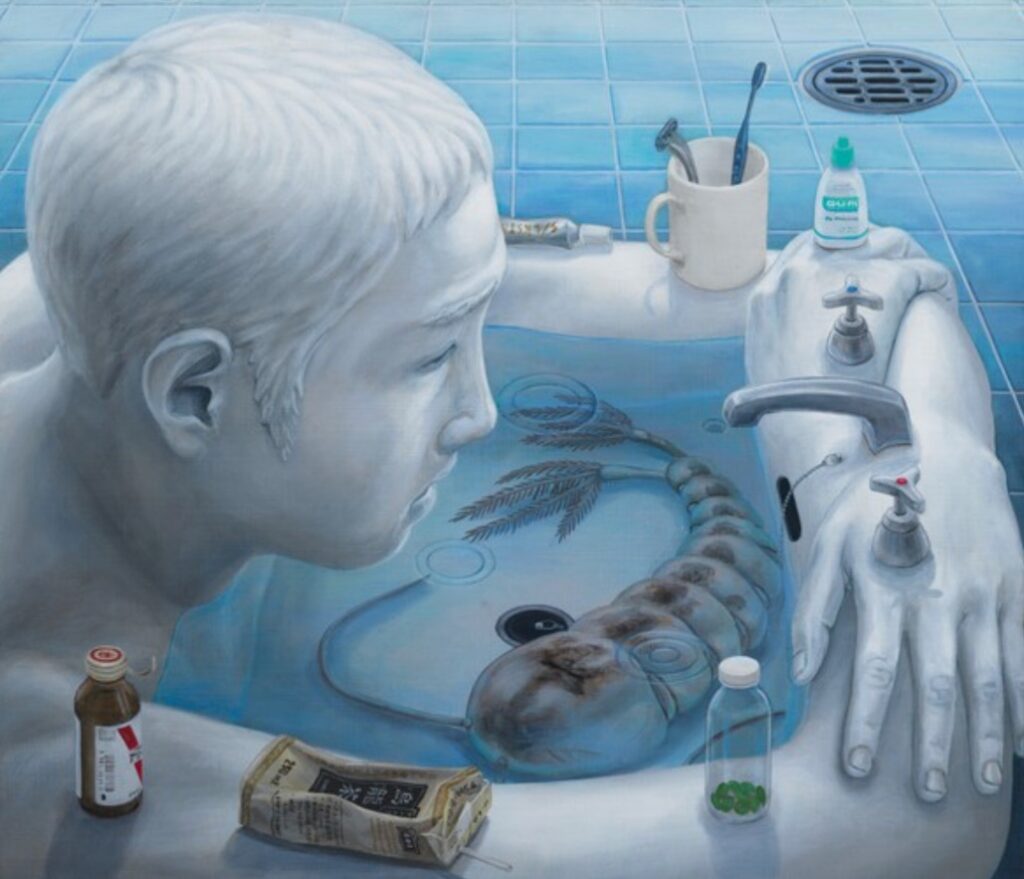

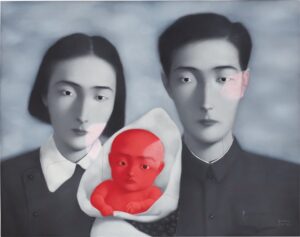

The works of Zhang Xiaogang, in particular, not only evocatively convey his childhood trauma and nostalgia, but also universalise the pain and suffering throughout the cultural revolution by giving a voice to the collective dreams and psychological unrest of an estranged generation. In his ‘Bloodline: The big family’ series, Zhang revisits the style of family photographic portraiture, a tradition all throughout chinese history that was destroyed during Mao’s Cultural revolution. Inspired by old family photographs, Zhang’s Bloodline works resonate with an uncannily enthralling aura that combines the poignancy of old photographs – what one can see as lost moments in time – with a disquieting surrealist style. One piece in this collection that encapsulates his exploration of not merely the oppressive regime at the time but also the conflict between individuality and culture is his portrait ‘Big Family: No.9”.

Visual Analysis

Existing between the collective vision of socialist China and his own dissonant voice, Zhang reopens a lost chapter of the past. Despite the impassive and icy stares of his three protagonists, the work does not coerce us into an emotional response or any reading of narrative; rather, the grey apparitions of the figures beckon silently as flat relics of a familiar history, now emptied of its currency and rendered obsolete.

Positioned around a baby, the young man and woman wear modest cotton jackets and conservative haircuts, customs indicative of the Cultural Revolution era. Around the right sides of the woman’s mouth, baby’s forehead and man’s eye, blocks or patches of red light resemble birth marks or perhaps create the illusion of aged film, yet can be interpreted as symbols of social stigma, or, alternatively, a lingering sense of the sitter’s self-assertion. The focal point of the piece however, is the baby illustrated in bright red. (While red has always been auspicious in Chinese culture, the use of the colour could be suggestive of the child’s self-conscious awareness of being born into an era of political turmoil, seeing that it acts as a stark reminder of the revolutionary red flag. This interpretation is made all the more striking considering that Zhang based the piece on a photograph taken on the occasion of his elder brother’s 100th Day celebration, injecting the work with a palpable sense of trepidation for the future.

On the other hand, Zhang’s proclivity towards this hue perhaps also references the ubiquitous Mao-era slogan, “the Red, Bright and Illuminous”.

What is most intriguing about the work is not merely how Zhang usurps the apparent objectivity of photography as a medium to explore subjective identity, memory and trauma, but also how Zhang uses the motif of red thread to explore the concept of “family” as something immediate and intimate but also something universal and common to all.

Red thread motif

Invoking the title of the series, barely perceptible red threads weave around the baby- connecting him to his parents and linking the father figure to a space beyond the limitations of the canvas, creating this oddly cropped composition.

Throughout the Bloodline series, Zhang ingeniously references Mexican painter Frida Kahlo’s use of red lines such as in the shared veins of The Two Fridas (1939). Though Zhang’s ‘bloodlines’ evoke the universality of memories of the Cultural Revolution, these red threads also recall how during that period, children were urged to draw clear lines between themselves and their parents accused of transgression. Thus, in comparison to Kahlo’s explicitly exposed veins, Zhang’s ‘bloodlines’ are more elusive in meaning, denoting both the familial relations between figures and the troubling chains that restrain them behind the scenes. Ironically, red threads are a common symbol in Chinese folklore to allude to threads of fate and marriage, supposedly symbolizing happiness, filial piety and love. The distortion in the meaning of the red thread perhaps also parallels the destruction of traditional Chinese values against a backdrop of social and cultural change.

Thus, while Zhang depicts his own personal narrative, Bloodline: Big Family No. 9 can be interpreted as illustrative of a nation’s memory, where traditional values were replaced with allegiance to the communist party, and where symbols of love were replaced by universal reminders of Maoism.

Impact in society

Yet, reading the Bloodlines series through the lens of the psychological trauma resulting from the Cultural Revolution does not comprehensively elucidate the emotional power of the work. Through Zhang’s repeated exploration of the once lost concept of individuality, the blank expressions, exaggerated by the similar facial features of all members in the work, more so invite viewers to fill the void within the image with their subjective stories, experiences and reflection.

Zhang has written that these figures represent “souls struggling one by one under the forces of public standardization (with) faces bearing emotions smooth as water but full of internal tension” a description not necessarily having only to do with the cultural specificity of China at the time but could also reveal the global issues affecting change in the world today, calling into question the wider purpose of art as a way to reflect society and culture.

Art and culture

In our increasingly globalized and technologically advanced society, we often overlook art as a force for change, forgetting it is the purest form of expression and individuality. In facilitating understanding between communities, preserving history and even playing a key role in shaping the way we think, art is a reflection of change.

In Zhang Xiaogang’s bloodline: Big Family No. 9, we may not relate to the stifling and oppressive emotions conveyed, or fully understand the figures’ individual histories and unnerving nuances, yet we resonate with the lingering sense of nostalgia and hazy emotional undercurrents. We empathize with those who have been stripped of their voice to tell their story. We remind ourselves of our own beautiful, cultural heritage. Most importantly, in this work, we see history told through crystallized snippets of the past on a canvas.