'A Room of One's Own': Woolf and Gendered Constraints

by

Alice Rothwell

‘Women have served all these centuries as looking glasses, possessing the magic and delicious power of reflecting the figure of man at twice its natural size.’

This eloquent and fiercely critical extract from Virginia Woolf’s extended essay ‘A Room of One’s Own’ articulates an essential conflict between the capabilities of women, and their inability to pursue them under societal constraints, which she demonstrates to be intertwined with the focus of the essay’s study: ‘Women and Fiction.’

The statement itself is rich in praise of women. She rightly claims that they have ‘served’ for ‘all these centuries’, alluding to the narrative associated with marriage, where the woman would be assigned to a male superior, and fulfil domestic and reproductive duties, usually for his satisfaction. The analogy of a ‘looking glass’ holds a twisted truth, an archaic term for a mirror, an object with the purpose of ‘reflecting puts forward the idea that the woman’s function was to reinforce the male sense of superiority, by enabling them to command influence over an inherently weaker individual, even if this is subconscious as the essay later suggests. The image simultaneously draws upon the paradigm of women’s beauty which was, at the time, foregrounded by delicacy and elegance; this unfortunately promoted their objectification (accentuated by the fact that ‘looking glasses’ are items which can be owned), limiting them from pursuing academic careers, or careers whatsoever, and meant that their primary value lay in their outward appearance or reproductive potential: all notions that Woolf rightly condemns.

Whilst her criticisms are compelling in their own right, Virginia Woolf’s palpable enthralment with the powerful beauty and intellect of the woman, is what renders this such a striking quotation – one that certainly stood out to me as I read the book. She depicts women to be possessed of a ‘magic’ and ‘delicious power’, referring with sarcasm to the relentless sexual appetite of men, who often drive themselves under the dominion of their female counterparts through their impulses and desires. Further, her use of ‘magic’ epitomises the almost inexplicable beauty, psychology and experience of being a woman, something which supposedly appears alien, yet tantalising to the men, whom she portrays as rudimentary by comparison. Juxtaposing their sense of entitlement, men are simply creatures of the earth, with a modest ‘natural size’, which works to emphasise the depth and allure possessed by the magical woman, that far exceeds the man, despite society’s deep-seated prejudice and mistreatment.

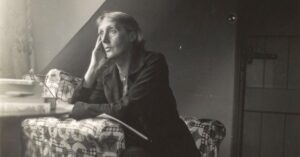

More broadly, I feel that this quotation is a reflection of the tone of Woolf’s work, one that seems to blend the narrative and argumentative, and encapsulates the growing dissent from traditional patriarchal attitudes during the early 20th century, which had overcast how women were presented in fiction, as well as their ability to succeed in the field of literature. If further persuasion is required for you to read ‘A Room of One’s Own’, I found it provided a fascinating insight into Britain between the world wars, through the lens of a bold and perceptive woman, whose prosaic voice is unashamedly feminist and unsurprisingly, has allowed her to become a preeminent literary figure of the 1900s.