‘Herstory’ of Art

by

Nadia Sun

Throughout history, women have been deprived of rights, respect, and recognition. This is no exception in the art world. For Women’s History Month and the topic of Women’s Voices, I present an unsung artist to hopefully shed some light on her story and magnify her artistic voice.

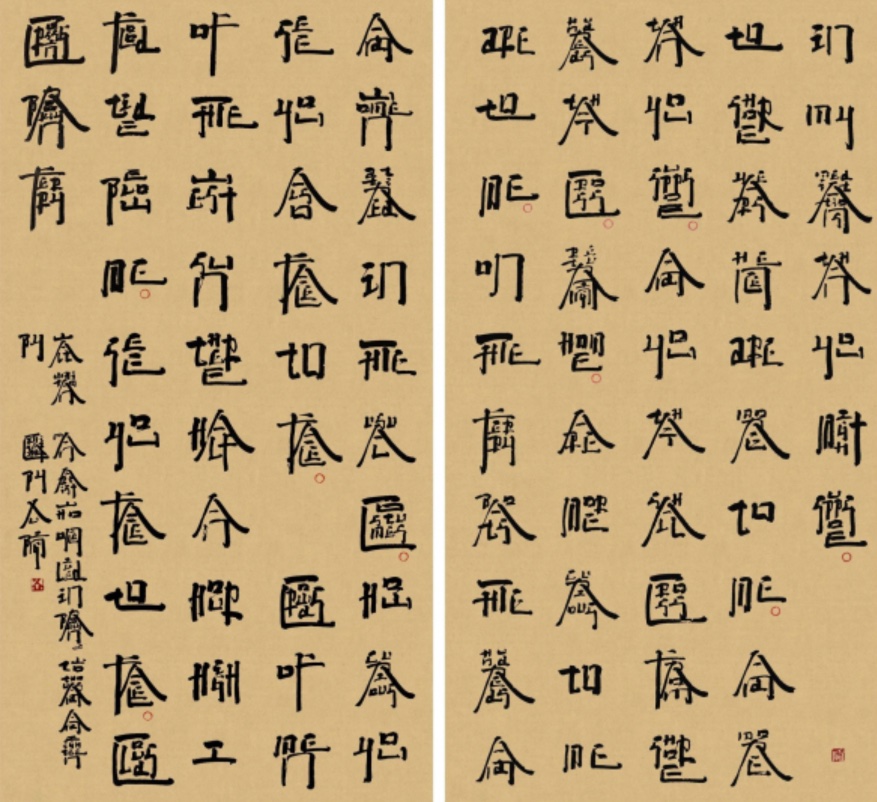

Katsushika Oi (Kanji: 葛飾応為)

Oi’s life is shrouded in uncertainty, to the point the dates of her birth and death are unresolved – although, it is widely accepted that Oi was born in 1800. Also known as Ei or Eijo, she was a talented painter and one of the few recognised women artists of the Edo period (1603-1867). Growing up with an artist as a father, Oi was exposed to the practice as a child, and though she spent her entire life creating, there are less than 15 works attributed to her name specifically. She excelled especially in the woodblock printing of the ukiyo-e genre of the time, her most common subject being bijin-ga (depictions of beautiful women).

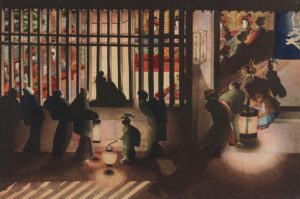

As a person, Oi was very progressive; she drank, smoked, got divorced, and had many relationships following her divorce. Her avant garde mindset and lifestyle manifested in her art, particularly in this painting below (“Display room in Yoshiwara at Night”) that illustrates a taboo topic of prostitution from the outside of a brothel. Not only does this picture offer us a less parochial view of Japan at the time, it also demonstrates her artistry with a sophisticated play of light and shadow (not dissimilar to chiaroscuro – an Italian technique) that was pretty much unseen in Japan.

After Oi’s divorce, she worked as a production assistant to her father. They worked closely together for a little over the last two decades of his life, so closely that it’s rumoured she may have even worked as his “ghost brush” (a similar concept to ghost voices/ ghost singing/ ghosting in the music industry). Publishers were aware that in placing an order to the pair one may receive work from either father or daughter. Some specifically asked for Oi’s services. However, the final product was inevitably signed with her father’s name, which may explain why Oi’s official oeuvre is rather limited. Art historians speculate that it was simply because the family brand sold better on the market, and also because Japan, like the rest of the world, was resolutely patriarchal, making his name more appealing. It’s tempting to theorize which artworks were wrongfully attributed to her father (especially those created towards the end of his 90 year old life which remained at a high standard and became increasingly innovative), but there is little to no evidence to prove hypothesises.

Oi’s father was (Katsushika) Hokusai.

In many unfortunate cases, female artists have been reduced down to the title of “daughter”, “pupil”, “assistant”, “muse”, “lover”, and “wife”, when they should in fact be acknowledged in their own right. I hope this short piece on Oi has inspired everyone to look out for those women who were overshadowed by the men in their lives and deserve more appreciation.

Here are some of my suggestions:

Artemisia Gentileschi (links to Caravaggio and Orazio Gentileschi)

Camille Claudel (links to Rodin)

Frida Kahlo (links to Diego Rivera)

Georgia O’Keeffe (links to Alfred Stieglitz)

Judith Leyster (links to Frans Hals and Jan Miense Molenaer)

Lee Krasner (links to Jackson Pollock)

Margaret Keane (links to Walter Keane)