Selling Sentiment – How Fashion’s Relationship with Nostalgia has changed.

by

Nadia Sun

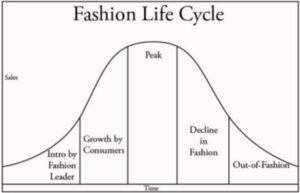

It is a widely known truth that fashion returns in cyclical terms, and this is largely credited to its tie with sentiment. When a new generation dominates the workforce, elements from decades prior resurface as people begin to reminisce about their childhood.

Using established ideas in new pieces is by no means a recent development and can be called ‘appropriation’ (fine art), ‘sampling’ (music), ‘retellings’ (literature), ‘sequels”/ “reboots’ (film), or ‘referencing’ (fashion). The sheer number of industry-specific terminology for the same concept indicates that obsession with the past is a theme not only limited to fashion, but rather present in all areas of expression. It’s even seen in theatre, architecture, photography, and internet culture.

So, while this isn’t anything new, it’s been noted that in the past few years (2020 – 2023), the cycles of reintegrating old trends have been shortening; nostalgia has skyrocketed, with almost every collection and garment around based on another “era”. Additionally, brands that were popular way back when gain sudden traction. The length of time before items become relevant again has dramatically decreased, exemplified by the recently come and not-quite-gone Y2K trend (dating back only 20 years). Inevitably, it seems even the 2010s are coming back into fashion…

It’s not only the time frame that has morphed. The types of things that fall in and out of fashion have changed, too. Arguably, until massive globalisation due to improved technology, specific silhouettes and features influenced people on a national scale. For example, during the Rococo era (France, 1720s – 1780s), a style of dress called the robe à la Française originated. It had a hold over high society for at least 10 years. Characterized by its tight (in the front) bodice, low cut neckline, and extremely wide pannier undergarments (and I mean extremely wide: we’re talking up to 5 feet), it was the precursor to other dresses across Europe like the robe à l’Anglaise. The Rococo era in general was extravagant, known for its pastel colours, box back pleats, and plethora of lush ornaments such as bows, frills, lace, and ruffles.

All in all, a go-big-or-go-home mentality.

The long pleats of the Rococo era were revived in the 19th century in simpler gowns as pictured below. They were often referred to as “Watteau” backs/ pleats/ trains/ dresses in recognition of the famed 18th century painter Jean-Antoine Watteau who created many portraits focusing on the loose backs of gowns.

Until recently, a major style revolution only happened after a long time, ranging from one decade to a few centuries. Fashion history was filled with big movements, the main dividing factor being class/ wealth rather than individualism. In contrast, the things that trend nowadays have narrowed down to specific items, with groups of people coveting after different items (e.g., claw clips, bike shorts, cowboy boots, Vivienne Westwood necklaces, cargo pants, crocs). Numerous trends exist and spread simultaneously, many styles taking hold globally.

It’s common to seek inspiration from the past and make something original out of it. However, intentionally producing clothing that copy-and-pastes old styles under the guise of nostalgia is now the main way fashion interacts with the past. The reason commodification and commercialisation of nostalgia through clothing works is simple. Most people enjoy being nostalgic. By recalling the past, we get to look back on a time and place through the lens of hindsight. It’s bittersweet and somewhat gratifying to reminisce about important moments and compare how our lives have changed. And while one could dwell on negative experiences, it’s more likely that you choose to think about the positives and come out happier after taking a trip down memory lane.

As a result, nostalgia can also be used as a coping mechanism for whatever draining situation is going on in the present. We’ve already been through that period of our lives; The past is comfortable as we already know what happened and can decide which moments to visit at will. During times of stress, turmoil, or change, it’s calming to escape back to somewhere stable and wallow in fond memories. That’s probably why some people watch the same shows over and over again: it’s comfortable. It’s stable.

The uncertain present and future that COVID-19 brought for the past few years was undeniably stressful, throwing the whole world into turmoil and change. Also, with lockdown to various degrees, everyone obviously spent a lot of time cooped up and living inside their heads. Combine all that panic and bleakness together, people were bound to turn to nostalgia for better times when families weren’t split apart, you could freely go outside – travel, even, and life was much simpler. That is a big part of why clothing has been an amalgamation of all the years before 2019.

Producing clothing that confronts consumers with a tangible piece of their past invites them to engage with nostalgia. They’re super effective visual aids that compel people to relive whatever they want to relive. Replicas of things from one’s childhood, adolescence, university life etc. trigger a reflection on the memories associated with those things. Therefore, it makes customers more likely to buy products because there’s some emotional connection and response to the time that that item represents. It’s an extremely rewarding strategy, and the profitability of it increased exponentially after COVID-19 hit. Nostalgia makes people happy, sure, but when COVID-19 came along, people actively wanted to feel nostalgic. There was no need to trip people into thinking of their past, everyone was already doing that. The market was prepared to buy into it, and so, everything “old”(er than covid-time) boomed as brands caught on and churned out items to feed into this need for the safety of the past.

I wrote a few paragraphs back that “During times of stress, turmoil, or change, it’s calming to escape back to somewhere stable and wallow in fond memories.” But that’s the thing. “Fond memories” are not all that the past is. Nostalgia gives us so much joy because it’s not an exact depiction of the past; it’s just the good excerpts compiled into a montage. Even without memory being as shaky as it is, people tend to glorify their “past” since we’re in control of which memories we deep dive into. It’s real, but not close to the whole picture.

And so now, the authenticity of commercial “nostalgia” must be addressed.

It’s natural to relate to a piece of clothing if it reminds you of your past; however, as demonstrated by the Y2K trend – of which Genz are the driving force behind (ages 8 – 23), it’s also possible for people to identify with a time they didn’t exist in or when they were too young for the culture to be part of their formative experiences. Logically, there is nothing to feel nostalgic about, so where does this bond that companies capitalise on come from? In fact, it is similar to true nostalgia in a fundamental way.

In the same way people glorify their pasts, it’s weirdly easy to glamourize an era which one has no connection to whatsoever. You can selectively reminisce, cherry-picking your way through the aesthetic parts of that time to make an ideal highlight reel that seems better than real life. And it is better than your real life and the real life of that era. It’s perfect because you’re romanticising a time and place you haven’t lived through. Your perception of that period is untouched and therefore can be shaped exactly how you want it to be. It’s catered to your rose-tinted glasses.

To pull out an exemplar manifestation of this phenomenon, the popularity of Cottage core and Regency core soared during the pandemic. Lockdown life in cities created the desire to escape. The simplicity and romance of country life or intrigue and lavishness of aristocratic life seemed far more interesting and safe than concrete jungles and urban confinement. Especially in the case of Cottage core, the aesthetic extended beyond looking the part and crept into mindset and lifestyle. Look up #cottagecore on any social media platform and an onslaught of posts entitled “Choose your escape home” or “Imagine if I ran away to the woods and just baked bread, gardened, and embroidered for the rest of my life.” will greet you. Although it’s all very illusory, indulging in one’s imagination to deal with daily life and make something special out of the mundane/ better out of the frightening may be beneficial for one’s mental health. There is nothing inherently wrong with that, and these “cores” serve as modern escapism which brought comfort and joy to many living through lockdown.

On the other hand, there is the issue that it puts us in an odd position to view history from. In romanticising a time and place that has happened, one is, whether consciously or not, ignoring the harsh realities hiding underneath the aesthetic. Take Regency core, catapulted into popularity by period dramas like Netflix’s Bridgerton, which is inspired by the Regency era (early 19th century). On the surface, it’s all about historical glamour, careful colour coordination, and regal patterns: totally harmless. However, people don’t think to ponder how there were divisions of class and gender and race and sexuality. Because that’s not fun anymore.

Global top lists of trending items in 2022 (compared to an average month in 2021):

Regency Core

- Corset (+117% in Aug)

- Opera gloves (+56% in Sep)

- Pearl earrings (+50% in Feb)

- Pearl necklaces (+32% in Feb)

- Feather headbands (+25 % in Sep)

It’s a little too easy to see these periods as so distant it feels novelty; that, because it’s in the past it’s all foreign and exotic and without negative aspects. Pretending life was better than now borders a little close to reconstructing history into something that it is not. Nevertheless, the pros and cons of investing yourself in a time period do not affect the overarching point: this longing for a time one never knew… is not nostalgia as most know it. It is as recently prevalent and marketable as the true nostalgia which does exist and propels contemporary fashion (buying goods reinforces this idyllic fantasy into something more real in the same way buying goods can take you back to your childhood), but it’s… nostalgia-esque at best. Nostalgic appropriation?

It’s possible that in this context, nostalgia has now taken on another meaning that equates to feelings of alienation and the desire to escape said alienation, rather than sentimentality for one’s past. The etymology dates to the Greek words νόστος (nostos – return home) and άλγος (algos – pain), combining to mean a pain to return home (thank you Gratin). Perhaps nostalgia can be used to capture a sense of homelessness, creating this idea of not having a place to call home and return to but still yearning for it in vain. Perhaps it can resonate with a sense of not belonging where you are, spurred on by a sudden change in life, wishing there was a place of warmth and acceptance like before.